If you’ve been learning French for any time, you’ve probably noticed that spoken French isn’t just written French spoken out loud. But school French isn’t really used in everyday conversations. For example, we never use le passé simple. Let me explain, with examples of what to use instead.

C’est parti!

Get more lessons every day, with daily fun practice, culture and game, and a nice community of other learners just like you! Learn more about our upcoming 30-Day French Challenge.

Index:

1 – Don’t use “le passé simple”

2 – Your turn now: Practice!

3 – Final Challenge

1 – Don’t use “le passé simple”

Today, I want to focus on practice to help you really get the hang of things. But let me explain a few things first so we’re all on the same page.

Le passé simple is a grammatical tense for an action that happened in the past. It’s the tense for narration and novels, like

- Soudain, elle chanta. = Suddenly, she sang.

- Vous écrivîtes. = You wrote.

- Nous partîmes. = We left.

- Je fus. = I’ve been, I was.

Yes, it’s called simple past, but it sounds complicated and weird. It’s part of why we don’t use that tense in spoken French. You’ll only hear it in formal narration, old settings or theater plays.

So you will never need to use it. Le passé simple is too formal for emails, letters, Internet writings, and everyday spoken French like real conversations.

So anyway, what do we use in everyday life instead of le passé simple? Well, we use le passé composé of course! You probably heard about that tense when learning French in school.

It’s called “composé” because it’s made of two parts: “avoir” (= to have) in the present tense – or sometimes “être” (= to be) for some verbs. And then le participe passé (= the past participle). For instance,

Elle a chanté. = She sang.

It’s built like the present perfect in English: “She has sung.” Except it simply means “she sang.”

OK, now I can hear you say: “Wait a minute, “le passé composé” looks more complicated! Is it more regular than le passé simple, at least??”

And the answer is: “…well, barely.”

On the one hand, you have to learn the past participles of the verbs, like chanté = sung, mangé = eaten, or parti = left, and the past participle of partir = to leave. Some of them can be quite irregular, and there are some special rules on top of it.

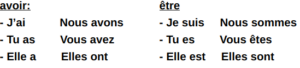

On the other hand, you probably already know the conjugation of avoir and être in the present:

> Le passé composé is a compound past tense in French, and it is commonly used to express completed actions or the actions that took place in a precise moment in the past, whose duration we know: we know when the action started, ended or for how long it lasted.

1. Using “Avoir” as the Helping Verb:

- Most verbs use “avoir” as the helping verb in the passé composé.

- The past participle is usually formed by adding “-é” for -er verbs, “-i” for -ir verbs, and “-u” for -re verbs, but there are a lot of irregular past participles.

- Agreement in gender and number is not required when “avoir” is the helping verb, but only in specific cases.

- J’ai mangé. = I ate.

- Tu as fini = You finished.

- Il a vendu = He sold.

- Nous avons parlé = We talked.

- Vous avez écrit = You wrote.

- Elles ont choisi = They chose.

2. Using “Être” as the Helping Verb:

- Certain verbs, often related to motion or a change of state, use “être” as the helping verb.

- The past participle agrees in gender and number with the subject when “être” is used.

- Je suis arrivé = I arrived. (a man)

- Tu es tombé(e) = You fell. (a man or a woman with the additional “e”)

- Il est parti = He left.

- Nous sommes nés/nées = We were born.

- Vous êtes monté(e)s = You went up. (the additional “e” for a group of women)

- Elles sont venues = They came.

> L’imparfait (imperfect) is another past tense in French, and it is used to describe ongoing, habitual, or repeated actions in the past. Unlike the passé composé, which focuses on completed actions, the imparfait provides a continuous or background description of past events. Here are the basic rules for forming and using the imparfait:

- For regular “-er”, “-ir”, and “-re” verbs, the imparfait is formed by removing the “-ons” ending from the present tense “nous” form and adding the imparfait endings: “-ais”, “-ais”, “-ait”, “-ions”, “-iez” and “-aient”.

- For irregular verbs, the conjugation must be memorized.

- Je parlais = I was speaking

- Tu habitais = You were living

- Il allait = He was going

- Nous dormions = We were sleeping

- Vous regardiez = You were watching

- Elles jouaient = They were playing

Remember that while the passé composé and imparfait are past tenses, they serve different purposes. The passé composé is used for specific, completed actions, while the imparfait is used for ongoing or habitual actions and to set the scene in the past. These two tenses are often used in a narrative to view past events comprehensively.

Click here to learn more:

- How to master le passé composé when speaking French

- How to Know Which Past Tense to Use in French: Passé composé vs imparfait vs passé simple

- French Past Participle: Verb Conjugations Rules & Tips

- L’imparfait: When and how to use it in everyday French

- French Conjugation: 6 Verbs That Use Both “Avoir” And “Être”

2 – Your turn now: Practice!

So, let’s have some fun with French grammar. You can practice with me right now at home while watching this video behind your screen.

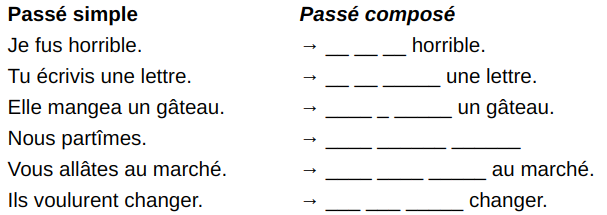

Let’s get used to hearing some “passé simple” so you can understand what’s happening when they use it in formal French. But let’s also practice le passé composé together – so you can become more confident in the everyday French we speak in real conversations.

1/6 Elle mangea.

It’s in le passé simple. You might wonder why there’s a silent “e” in there, and that’s a good question. It’s there to remind you that it’s a soft “g” sound, as in “giraffe”, and not a hard “g” as in “gift.”

And what do you think it means?

Yes, it simply means, “She ate”! As in “Elle mangea du fromage.” = She ate some cheese.

But we would never say it this way in everyday spoken French. How would you say that in le passé composé? We would use “Elle”, of course. Then “avoir” in the present, then the past participle for “manger.” We mix that, and we get…

Elle a mangé. = She ate.

“Elle” for “she”, “a” for “avoir” in the present, and “mangé” for the past participle.

2/6 Je fus timide.

Je fus timide. = I’ve been shy, or I used to be shy.

How would you say that in everyday spoken French?

You might already have the answer. Or do you need a refresher on past participles? The one for “être” is “été.” Yes, it’s like l’été, summer! And our sentence finally makes:

J’ai (= Je + “ai”, avoir) été (past participle) timide.

J’ai été timide. ! = I’ve been shy, I used to be shy.

You can also add any other adjective, from superbe = incredible to horrible = terrible.

3/6 How would you write in passé simple the sentence “You wrote a letter.”?

Here, we’ll use the regular verb écrire = to write. What do you think the passé simple conjugation looks like for “tu”? It’s:

– Tu écrivis une lettre. = You wrote a letter.

How would you say that in the passé composé? It’s pretty straightforward. The past participle for écrire is simply écrit, written. So it makes…

– Tu as écrit une lettre. = You wrote a letter.

You can pause the video and try the same exercise with the verb rédiger = to edit and write instead of écrire. It’s just like manger!

Here are the answers:

– Tu rédigeas une lettre.

– Tu as rédigé une lettre.

4/6 What do you think is the conjugation of that sentence, “Nous partons”, in le passé simple? It is…

Nous partîmes. = We left.

How would we say that in le passé composé, though? Do you remember the past participle of partir? We’ve seen it together earlier: it’s parti.

But there’s one more thing here: this verb, partir, uses “être” for le passé composé. So what do you think it looks like with “nous”? It is…

Nous sommes partis.

It’s become Nous sommes, the present conjugation for “we are.” More importantly, you can notice that “partis” has a silent “s” here; it’s in the plural. That’s the special rule of passé composé: for the few verbs that use “être” instead of “avoir”, the past participle agrees with the subject.

By the way, in real, everyday spoken French, we would not use “Nous” at all. Instead, we’d say: On est partis. = We left with the informal pronoun for “we”.

The agreement of the past participle:

- “On est parti.” is allowed because “on” is third-person singular;

- “On est partis.” is allowed because it’s used as the plural “we” with other people.

Now, we’ll see the sentences that all mean the same thing, but from the most to the less formal ones:

- Nous nous trompâmes. (le passé simple)

- Nous nous sommes trompés. (le passé composé, with the “nous” pronoun)

- On s’est trompés. (le passé composé, with “on” pronoun instead of “nous”)

- On s’est gourés / plantés. (le passé composé with “on” pronoun and the slang verbs “se planter”, “se gourer”)

Click here to learn more:

Why You Should Never Say “Nous” in Spoken French (Improve Your Fluency)

Le truc en plus:

Le parti = the (political) party, the side of a debate.

Une fête = a party.

5/6 Le passé simple is Vous allâtes au marché. = You went to the market. with the verb aller = to go.

The passé simple with “Nous” and “vous” always sounds quite weird to a French person. We rarely find sentences like “Nous partîmes” or “vous allâtes.” We primarily use passé simple for narration in novels, mainly in the third person, like “He” or “They.” But the characters themselves don’t use it often!

So how would you say that, “vous allâtes au marché,” in everyday passé composé instead? It uses “être”, again…It’s:

Vous êtes allés au marché ! = You went to the market.

Or if only women are in the group, we would add a silent “e” to make the past participle feminine: Vous êtes allées au marché!

Allé agrees with the subject and becomes plural or feminine or masculine because with “aller”, we use “être” instead of “avoir”! And the same thing happens with “elles”, the feminine “‘they”, with the verb aller = to go.

Elles allèrent au marché. = They went to the market, they visited the market.

How would you say that in le passé composé ? We use “être”, so it makes… Elles sont allées au marché.

We simply use “être” with the plural “They”, and the past participle “allé” becomes allées to become plural and feminine.

6/6 Let’s try our hand at one last sentence: Ils voulurent déménager. = They then wanted to move, to live somewhere else.

How would you say that in le passé composé ? “Vouloir” (= to want) uses “avoir” for its passé composé, and becomes voulu in the past participle. So, it’s…

Ils ont voulu déménager. = They wanted to move!

3 - Final Challenge

How would you say these sentences in passé composé? Don’t look at the answers right below, until you completed your challenge!

As we’ve seen, le passé simple is an important part of formal, written French. But it’s not the language of everyday spoken French. So you can learn about le passé simple in school and how to read French books or plays, and it’s great. But you can also forget about it, skip the conjugation tables, and talk directly to French people to have real conversations! The essential idea behind all this is that written French and informal everyday spoken French can sometimes be seen as two different languages altogether.

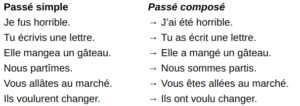

Answers for the Final Challenge:

That’s the kind of practice and exercise you’ll also find in my longer courses, with programs from intermediate to advanced, such as French Conversation with Confidence, French Vocabulary & Pronunciation – or the 30-Day French Challenges almost every month! They’re all enjoyable, with our lovely community of open francophiles, and they’re designed to help you find confidence whatever life in France throws at you.

Here are the links:

– FRENCH VOCABULARY & PRONUNCIATION (course)

– FRENCH CONVERSATION WITH CONFIDENCE (course)

Or you can keep watching to get your next session of French Pronunciation Practice with me!

Click here to get your next lesson:

- Why You Should Never Say “As-tu ?” in Spoken French

- Modern Spoken French: How to Use “On”

- Spoken French Grammar: What You Say vs. What You Write

- Never Say “Mon Ami” in French (And What to Say Instead)

- French Grammar: French Subjunctive Made Easy

À tout de suite.

I’ll see you right now in the next video!

→ If you enjoyed this lesson (and/or learned something new) – why not share this lesson with a francophile friend? You can talk about it afterwards! You’ll learn much more if you have social support from your friends 🙂

I re read the lesson sent to me on the passe simple and the passe compose. I had loads of trouble as a adolescent with these terms. They are French of course. There was a great muddle in introducing these and then going to Latin for reference. Then German. Eventually, I settled on the wording for tenses in English, and the huge complication was eventually settled. Present tense or Indicative. Imperfect tense(i.e. not completed) Perfect tense (i.e. finished and complete.) Then conditional, Future, and subjunctive ( may) present. To start with giving passe simple which is the past Historic just causes so much muddle and confusion. Still worse the calling it the preterite.

The passe compose has no English aspect or is not good English. Best to call it the perfect tense. But it is also called the Past indefinite, or Compound past. It can be translated three ways, eg I have given or I gave. or I arrived, or I did arrive, but I have quitte la ville.hier…as to there cannot be so translated as I have left the city yesterday is not proper or good English. Giving all thee terms and names is so confusing. It’s was just impossible. Sticking to the terms I use is straight forward and preferable.

Of course there are more tenses too, pluperfect, past Anterior, conditional perfect Past subjunctive, pluperfect or past subjunctive pluperfect or past perfect subjunctive. Also present subjunctive and imperfect subjunctive. However, In my opinion we teach the basic seven, or leave the subjunctive ’til later and use six. My idea is learn the extra tenses when you have enough language to speak and start thinking about these complex tense structures. If a person can handle French or any other language at that level they are on track in working out the rest on there own.

I got the advice on the passe simple and the passe compose and thought oh, no, not all this again. Goodness! Being introduced to this confusion, puts people off the subject and giving up. I hope you don’t mind me expressing this, but it makes me so mad until I eventually found out what this muddle was all about and confusion in terms, with each different language, using different terms.

With regards. Olivier.

Good advice. I passed that earlier stuff and realised sometime ago that it was not the way. Once I got into the correct way of speaking I moved on easily. Thank you for the advice never the less. One piece of advice I may suggest that as a teacher you might not know. The Chinese way of remembering, Maxim: “I hear I forget, I see I understand and I do and I comprehend.” I did the lesson of the the 95 -phrases of social situation yesterday. Went thro them and a second time and then copied them out for the text you gave. Copying puts the text into the short term memory as per the maxim of the Chinese advice. The you remember it, even if you think you didn’t. When you come to it again it triggers your memory. I was a teacher of English for foreign persons. Regards, Olivier.

Unfortunately if you also read French books you need to know the passè simple !!

Wow…did I ever need this! It’s not yet intuitive, but makes so much sense now. Thank you!!!

Géraldine

You translate ” j’ai été timide” as I’ve been shy, I used to be shy. I would translate this as “I was shy”. And for ” I used to be shy”, wouldn’t this be the Imparfait, “j’étais timide”, to describe an ongoing past situation/ background information?

Vicki Anderson

(30 day challenge student)

Bonjour ! The video indicates “Ils ont voulu changer”. Should voulu be “voulus” in the case that the phrase is plural in subject?

Bonjour @Douglas M Basko,

That will not be necessary as the auxiliary is “avoir” and in this instance, there is no agreement with the subject.

Merci,

Fabien

Comme une Française Team