Je marchais dans la rue. = I was walking down the street.

In this sentence, “marchais” is in l’imparfait – the “imperfect tense” in French.

It’s used everywhere both in French culture and in everyday French conversations – it’s one of the main ways to talk about the past.

What does it look like? When should you use it?

What’s the difference with le passé composé ?

How can you train your ear to l’imparfait – and stay confident when you hear it in French conversations?

Let’s dive in.

Want all the vocabulary of the lesson ?

1) L’imparfait: What is it?

L’imparfait is the French version of the “past progressive” or “past continuous” tense: “was [verb]+-ing” etc.

For instance:

Je pensais à toi. = I was thinking about you.

→ Here the verb “penser” (= to think) is in l’imparfait. It makes “Je pensais.” = I was thinking

This is the gist of it. Of course it’s a bit more complicated than that, and we’ll get to some of that below.

But first, let’s take a look at its easy conjugation!

2) L’imparfait: Easy conjugation

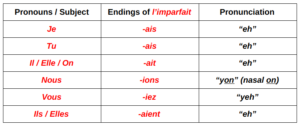

All French verbs have the same endings in l’imparfait! That’s very unusual in French conjugation, where there’s usually a ton of irregular endings.

They’re:

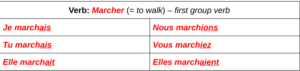

For example, for “I was walking / You were walking / …” you would use:

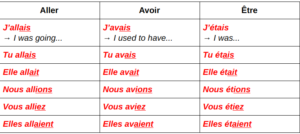

And it can also work for verbs that are usually irregular (third group), such as “Aller” = to go, or “Avoir” = to have. Even for Être = to be, even though it’s the only verb where the stem is technically irregular.

** Le truc en plus **

In everyday spoken French conversations, “Tu allais” / “Tu avais” / “Tu étais” often gets shortened into “T’allais” / “T’avais” / “T’étais”, because French people “eat” letters.

****************

You can do the same thing for almost any other verb!

- Take the stem (= the verb in the infintive but without -ir or -er)

- Add the endings for l’imparfait

- Voilà !

3) L’imparfait: Deeper Conjugation (The extra mile that you can skip)

a) Root of 2nd-group verbs

Actually, there’s a bit of complication in “take the stem (or root) of the verb.” It’s not simply the infinitive without -er, it’s actually:

Root = verb in the present for “Nous,” but without “-ons”

It’s usually the same thing.

But it gives a better rule for verbs such as prendre = to take, for instance.

Prendre → Nous prenons (= we take) [present] → Je prenais, tu prenais, il prenait… [imparfait]

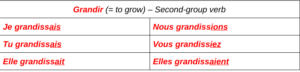

That rule also gives use the imperfect for second-group verbs. Second-group verbs are verbs like grandir (= to grow up, to get taller):

- They have an infinitive in -ir

- With “nous” in the present, they make nous grandissons (= we are growing up.)

Take out the “-ons” and you have their root in the imperfect: grandiss-

So it makes:

Fortunately, there aren’t many second-group verbs in everyday French (grandir, nourrir = to feed…) – most verbs in -ir are 3rd-group (like courir = to run, dormir = to sleep…) Unfortunately, there’s no real shortcut; you have to learn the group of each verb in -ir you see.

b) Tweaks in first-group verbs, for pronunciation reasons

Verbs in -ger add an -e before the endings of l’imparfait, with all subjects except “nous” and “vous.” Basically, we don’t want to hear the hard “g” sound that would appear with “g + ais.” So we turn it into “-geais” [sounds like “jjay”]

Most notably:

Manger (= to eat) → Nous mangeons (= we eat)

→ In l’imparfait:

Je mangeais Nous mangions

Tu mangeais Vous mangiez

Elle mangeait Elles mangeaient

Same thing with verbs in -cer. We add la cédille (ç) for all subjects with -ai-.

So it always sounds like “ss” (as in “ça” or “ce”) and never like “k” (as in “ca” or “co”).

Most notably:

Commencer (= to start) → Nous commençons (= we start, present)

→ In l’imparfait:

Je commençais Nous commencions

Tu commençais Vous commenciez

Elle commençait Elles commençaient

c) Impersonal verbs

Some impersonal verbs don’t always have a present form with “nous” yet we still use them in l’imparfait. Most commonly:

Il y a (there is) → il y avait (there was / there used to be)

Il faut (Someone needs to…) → Il fallait (Someone needed to…)

Il pleut (it’s raining) → il pleuvait (it was raining)

Il neige (it’s snowing) → il neigeait (it was snowing)

4) Other uses for l’imparfait

Did you notice? In the examples above, I sometimes translated l’imparfait with “used to [+ verb].”

Well, that’s the second meaning of l’imparfait : a habit, in the past.

For example:

J’allais au bureau en voiture tous les matins. = I used to drive to the office every morning.

J’avais une voiture, avant. = I used to have a car, before.

More generally, it’s used for situations in the past (that lasted some time).

Like: J’étais déjà à Grenoble l’année dernière. = I was already in Grenoble last year.

And for long actions in the past:

Elle allait à la boulangerie, quand elle a vu Michel.

= She was going to the bakery when she saw Michel.

→ Here, “Elle allait” is a long action compared to “elle a vu.” “Seeing Michel” cut short her action of “going to the bakery.” That’s why we use l’imparfait for “elle allait,” and le passé composé for “elle a vu Michel.”

Le passé composé is the other main French tense for the past, and it’s used for short actions (that we take as a whole, rather than as a period of time.)

*** Le truc en plus ***

For long actions (= progressive tenses), you can also use the everyday expression “être en train de” = to be in the middle of [doing something].

For instance:

Je suis en train de manger. = I am currently in the middle of eating.

Elle était en train de sortir de la boulangerie. = She was in the middle of walking out of the bakery.

***** *****

(For the extra-extra-mile, as a simple French curiosity, there’s one last use of l’imparfait: l’imparfait “hypocoristique” = using l’imparfait in place of the present tense, to sound like you’re talking like a child, for endearment.)

5) L’imparfait: Your Turn Now

And now you can get confident in using l’imparfait!

How would you say in that tense:

- Elle pense à lui. = She’s thinking about him. [penser = to think]

- Ils vont à l’école. = They’re going to school. [aller = to go]

- Je suis sûre qu’il est là. = I’m sure he’s there. [être = to be]

Take your time to answer!

Did you get it?

Yes, it’s:

- Elle pensait à lui. = She was thinking about him. / She used to think about him.

- Ils allaient à l’école. = They were going to school.

- J’étais sûre qu’il était là. = I was sure he was there.

Congrats! Keep practicing and you’ll get more confident with l’imparfait in no time.

You can dive deeper with other lessons too, such as:

- Common French Verbs – The First 7 Verbs you should master

- French Conjugation with Le Passé Composé – Using both “Avoir” and “Être”

- Le Participe Passé – French Past Participle used in Passé Composé

À tout de suite.

I’ll see you in the next video!

And now:

→ If you enjoyed this lesson (and/or learned something new) – why not share this lesson with a francophile friend? You can talk about it afterwards! You’ll learn much more if you have social support from your friends 🙂

→ Double your Frenchness! Get my 10-day “Everyday French Crash Course” and learn more spoken French for free. Students love it! Start now and you’ll get Lesson 01 right in your inbox, straight away.

Click here to sign up for my FREE Everyday French Crash Course

It helped a lot, merci beaucoup 😊

Du courage. C’est un cours très superbe!

Du courage. C’est cours très superbe!

So subtle explanation.

Merci beaucoup.

I loved it 😍🥰

Est-ce que le genre neutre existe en français ?

par exemple Iels sont étudiant . e . s à l’école

Merci beaucoup. I love how you have the pronunciation of the endings.

Merci beaucoup. J’ai fini mes devoirs!

J’avais adoré cette leçon. J’espérais pour vous à un bon noËl

Thank you so much! This taught me much more than my teacher.

Merci. J’ apri beaucoup

Pourquoi est-ce que la langue française utilisé l’accent circonflex ” ^”

Bonjour Peter,

Tout commence en Grèce: « circonflexe » est né du grec « périspoméné », qui signifiait « tirer une corde de la lyre pour changer le son ». On mettait alors un petit chapeau pour indiquer la variante sonore.

Cependant, il n’est plus obligatoire d’apposer la marque circonflexe sur les lettres u et i depuis 2016. Les rectifications orthographiques de 1990, menées par le Conseil supérieur de la langue française et approuvées par l’Académie française, rendent facultatif l’emploi de l’accent pour ces lettres (on peut désormais écrire «maitresse, flute, huitre»).

L’accent circonflexe est cependant toujours de mise dans la terminaison de certains verbes (au passé simple), et quand il permet de différencier les homonymes («mûr, jeûne, sûr, dû»).

Bonne journée,

Fabien

Comme Une Française Team

Bonjour,

Comment utiliser le sujonctif en Français?

Bonjour,

Alors, c’est un peu complexe mais j’espère que cette réponse t’aidera un peu :

Le subjonctif sert :

à exprimer l’ordre ou le souhait dans une proposition indépendante. Ex : Qu’il vienne immédiatement ! (ordre) – Que tout le monde soit heureux ! (souhait)

à exprimer le désir, la volonté, l’exigence (vouloir, exiger) ou un sentiment (souhaiter, avoir envie…) dans une subordonnée (qui dépend donc d’une principale).

Ex : Je veux/Je souhaite/J’exige/J’ai envie que tout le monde soit heureux.

On le trouve après de nombreuses expressions : afin que, bien que, quoique, pour que, avant que, jusqu’à ce que, pourvu que…

Ex : Bien qu’il ne soit pas d’accord, il n’a pas discuté la décision.

On le trouve également après les verbes d’obligation : il faut, il est nécessaire que.

Ex : Il faut que tu apprennes ta leçon.

Le subjonctif en français ne s’utilise à l’oral qu’au présent (que je sois, que je vienne) et au passé (que j’aie été, que je sois venu). L’imparfait et le plus-que-parfait sont réservés à l’écrit et encore… Ces deux derniers temps sont jugés très littéraires. On ne dit pas et on écrit rarement : ‘… qu’il eût fallu que tu vinsses’ mais ‘….qu’il aurait fallu que tu viennes’.

Bonne journée,

Fabien

Comme Une Française Team

Merci beacoup pour répondre à mon question.

Peter Pham

Merci Géraldine comme toujours cet leçon est très utile. Merci beaucoup. Bonne journée

Anne

Merci à toi Anne !

Une excellente journée,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française

no

It’s lovely revision for me at 74. I remember so much. Started French aged 7. Can’t sign up for your recent offer as am a haphazard learner not wanting anything intense and requiring too much effort. Enjoy you immensely.

Snap Vanessa! I too am of a certain age and I am not able to give my all. Geraldine’s course is wonderful though. learning French is and always has been my favourite pastime.

Yes me too. I have for many years wanted to do a French course and was able to join one in my village but it has closed as our teacher was ill. Geraldine’s course is great. I had planned last year to go to Tours on s language course but Covid has out paid to that. I wanted to recapture those student years again but I do wonder if it is too late to fix new words in my brain!

Hi Vanessa,

That’s so lovely! Keep learning at your own pace, have fun and enjoy your day 🙂

Have a great day,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française

Merci Geraldine! J’ai étudié le français dans l’école, mais plusieurs années plus tard, j’avais une amie française qui m’a appris plus que le lycée. Elle est morte maintenant. C’est dommage. Elle me manque beaucoup.

Bonjour Randi!

C’est dommage 🙁 J’espère que tu vas bien.

Continue à apprendre et à laisser des commentaires 🙂

Passe une bonne journée,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française

Just a note: your video lesson had “vous étions” on the screen in the conjugation slide. You read it as “vous étiez,” so I thought you may want to correct it for future viewings. Hope this helps👍

Hi Judy!

Thank you so much for the feedback.

It is indeed a mistake 🙁 I’ll see if we can do something about it.

Have a great day and keep learning,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française

Do you (from Grenoble) pronounce “allais” and “allé” differently? I think I hear a little difference but I’m not sure. I’ve read some sources online that suggest that in Metropolitan French they tend to be pronounced the same but differently in Quebec.

Hi Keith!

There’s actually a lot in that question.

Short answer :

“allé”, just like “allez” and “aller” (and “fiancé”) ends in [ e ] (phonetic)

“allais”, just like “palais” or “Monet”, ends in [ ɛ ] (phonetic)

Longer answer:

I have no idea about the pronunciation of Québécois French. It’s very different in so many ways.

In France itself, basically everyone would pronounce “allé” / “allez” / “aller” the same way.

However, some people (especially with a Southern Accent) would also pronounce “allais” as ending in [ e ] (phonetic) as well.

Géraldine lives in Grenoble but grew up in the Parisian area so she has a Parisian accent (also most people younger than 40 speak with the Parisian accent anyway, especially outside of the South.)

Even longer answer:

– I don’t know all the local French accents, in the West, the East, around the Loire river etc. Maybe between the towns of Melun and Bar-le-Duc, young people carry the accents of their parents and have their own pronunciation. You can get nice surprises when exploring the diversity of local French.

– “J’allai” (= I went, in “le passé simple”) is even trickier : it’s supposed to sound as “allé” with a [ e ], but lots of people would pronounce it “j’allais.” Luckily (or maybe it’s the reason why), it’s not pronounced often – “le passé simple” tense is mostly used in written French, in novels especially.

Have a great day,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française

Super helpful. Thank you!

Hypocoristique? J’aimerais en voir un exemple s’il te plaît, Géraldine.

Hi Jane!

Disclaimer: Basically nobody knows the word “hypocoristique”, but I found it cool. Though the actual thing of “children talking in a special way” is common, of course.

Example:

“Comme elle était belle, la dame !”

= How pretty that lady was! (literally)

= How pretty that lady is! (in child’s talk – because the difference between tenses is difficult / it’s cute for a child to talk in the imperfect)

But that’s all a very minor point in the lesson, and an even lesser point of French language in general.

(The word “hypocoristique” is still cool though)

Have a great day,

– Arthur, writer for Comme une Française