Salut !

Le Musée d’Orsay is a fascinating museum in Paris, home of impressionist paintings like Claude Monet and more. Let’s explore it together – and use the occasion to learn about French numbers!

Let’s dive in!

Summary:

1) Au Musée d’Orsay : Introduction

2) Au Musée d’Orsay: Révolution Industrielle

3) Au Musée d’Orsay: La Gare Saint-Lazare (Claude Monet, 1877)

4) Au Musée d’Orsay: Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Édouard Manet, 1863)

5) Au Musée d’Orsay: Les Raboteurs de Parquet (Gustave Caillebotte, 1875)

6) Au Musée d’Orsay: Bal du moulin de la Galette (Renoir, 1876)

Want all the vocabulary of the lesson ?

1) Au Musée d’Orsay : Introduction

Le Musée d’Orsay is a famous museum and one of the most visited places in Paris. It became a museum in 1986.

Every year, it’s visited by:

entre trois et quatre millions de personnes

= between three and four million people.

Numbers: 3-4 million

- The “s” in “millions” is silent

- Un million, deux millions

It’s the museum with the largest collection of impressionist paintings in the world, with more than quatre-cent-quatre-vingts (480) paintings of that style.

Numbers: 480

- Cent = 100

- Quatre-cents = 400 (silent “s”)

- Vingt = 20 (silent “gt”)

- Quatre-vingts = 80

- Quatre-cent-quatre-vingts = 480

- No “s” in cent if there’s something after it.

- Same thing for 20 : Quatre-vingt-un = 81

→ You don’t have to remember all these rules, just pick the easiest one that you don’t know!

For complex numbers below 100 like Quatre-vingts (80), there’s always un trait d’union / un tiret (= a hyphen).

(For complex numbers above 100, the rule says to add an hyphen as well, since 1990. But some people still wouldn’t use it.)

Extra mile for numbers:

- In Belgium or Switzerland, they say “octante” for 80. It makes a lot more sense, but it sounds weird to a French person!

- En lettres = (a number written with) letters

- En chiffres = (a number written with) digits, or figures.

- Un nombre is a number, the concept of “three” or “five.”

- Un chiffre is the symbol we use to write that number, like the symbols “1,” “2,” “9” etc.

- Des Chiffres et des Lettres is a very-long-running French TV game show that alternates rounds of letter games and number games.

You can take a virtual tour of the museum online for free!

2) Au Musée d’Orsay: Révolution Industrielle

Le Musée d’Orsay has a collection of more than 600 post-impressionist paintings from France and abroad, as well as more than a thousand sculptures (more than 1500 of them, even.)

Numbers:

- Six-cents = 600

- Un millier = around a thousand (common noun)

- Des milliers = thousands

- Mille = a thousand exactly (invariable)

- Deux-mille = 2000 (no “s” in “mille”)

- 2022 = “Deux-mille-vingt-deux”

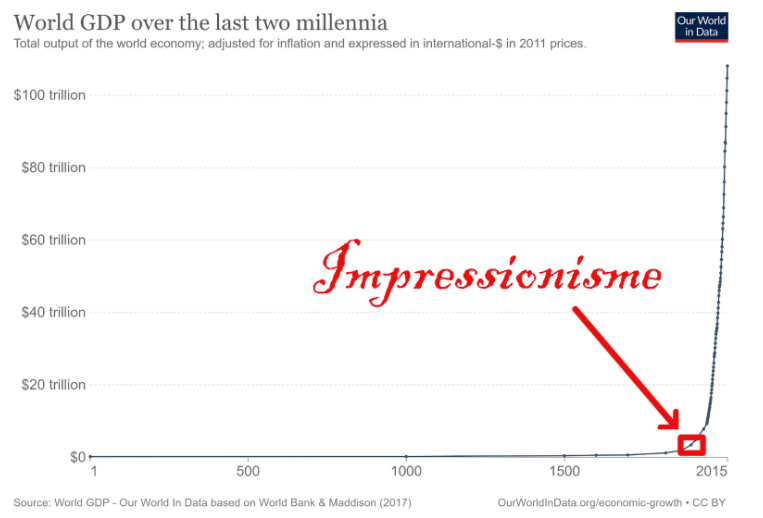

It’s a museum for the art of la Révolution Industrielle (= the Industrial Revolution.)

Yes, it’s when paint tubes were invented and painters could finally paint outside.

But it was also mainly a period of tremendous changes, with social, economical and technological changes that were never seen before.

3) Au Musée d’Orsay: La Gare Saint-Lazare (Claude Monet, 1877)

Of course, the central innovation of the period was trains.

One of the main impressionist painters, Claude Monet, did a groundbreaking series of paintings of the Parisian train stations la Gare Saint-Lazare.

This is le premier (1er) tableau, the first painting, of the series.

This work of art is appropriate for le musée d’Orsay, since the place used to be a train station!

Just like la Gare Saint-Lazare, the architecture of musée d’Orsay comes from around the year 1900.

It was the height of La Belle Époque, the “Beautiful Period” after the creation of train stations – but before the horrors of the Great War.

Nowadays, these buildings are a place to show the art from this period, between 1848 and 1914, a period spanning:

- la Deuxième République (= the second French Republic),

- le Second Empire (= the second French Empire, led by Napoléon III, the nephew of the previous emperor Napoléon),

- The first half of la Troisième République (= the third French Republic)

- Until la Première Guerre mondiale (= the First World War).

Numbers:

- 1900 = mille-neuf-cents

- 1900 = dix-neuf cents (“nineteen hundred”), an alternative pronunciation of dates in spoken French. The liaison in “dix-neuf” sounds like “z.”

- 1848 = mille-huit-cent-quarante-huit

- 1848 = dix-huit cent quarante-huit (same as 1900)

- 1914 = mille-neuf-cent-quatorze

Ordinal numbers: first, second, etc. :

- Le premier / la première (1er, 1ère) = “the first” (masc / fem)

- Le second / la seconde (2nd, 2nde) = “the second one” (masc / fem) but when there’s no third one. As in “La Seconde Guerre mondiale” (hopefully.)

→ The “c” sounds like a hard “g.”

→ Une seconde = a second (measure of time) - Le deuxième / la deuxième (2ème) → The second one when there’s also a third one after it, or more. The “x” makes a “z” sound, sorry!

For higher numbers: number + -ième after it. Feminine and masculine are the same.

- La troisième = the third

- Le vingtième siècle (le XXème siècle)

- Le dix-neuvième siècle (XIXème) → The “v” sound of the liaison of “neuf” (9) becomes part of the actual spelling.

For an indeterminate amount, we sometimes say l’énième (sounds like “n-ième”), the “umpteenth time / nth time.”

4) Au Musée d’Orsay: Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Édouard Manet, 1863)

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, (= Lunch on the grass), by Édouard Manet (not Claude Monet!) was a scandal.

Usually, nude women were restricted to mythology, like Greek nymphs and more. But here, the painter mixed them in a modern bourgeois setting. That’s new!

This is not an impressionist painting – it’s more in the style of realism. But really, it’s above all one of the first paintings of modern art – playing with and breaking the conventions of what should be art, and trying to change the hypocrisies of contemporary society.

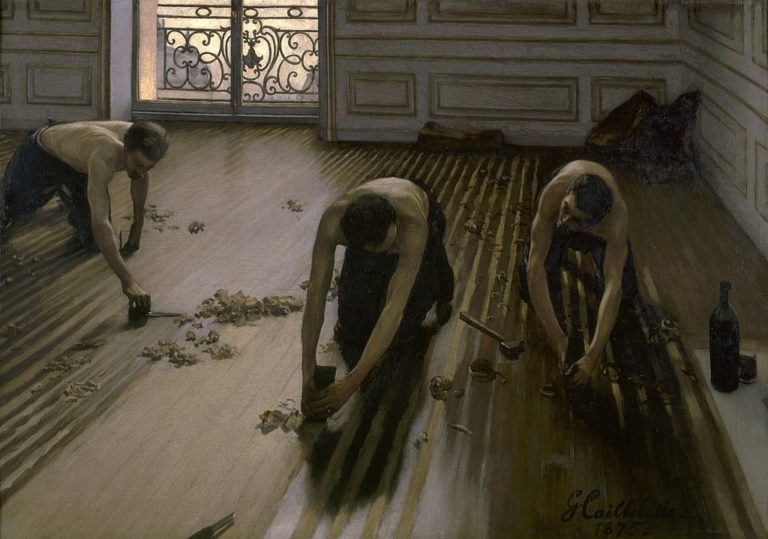

5) Au Musée d’Orsay: Les Raboteurs de Parquet (Gustave Caillebotte, 1875)

With Les Raboteurs de Parquet (= The floor planners), Gustave Caillebotte tried his hand at some social painting.

That too wasn’t “allowed” by the official art critics of the time!

Scenes of working class people as they actually work was frowned upon.

To be honest, when we think about realistic depictions of lower-class French society in the XIXth century, we don’t think about painting. We think about literature, and the movement of le naturalisme that happened around the same time as l’impressionnisme in painting.

Especially with journalist and author Émile Zola, and the twenty novels of his series Les Rougon-Macquart, where he covered the misadventures of a family living through the XIXth century social and technological transformations: trains, coal mines, urban life, political struggles, the wonders of the new general stores, and much more.

*** Le truc en plus ***

In the video, I show a clip from the amazing series of TV shorts “A Musée Vous, A Musée Moi”, click on the link to check it out! The title is a pun and sounds like “Amusez-vous, amusez-moi” (= have fun, entertain me) – but with more museums.

***

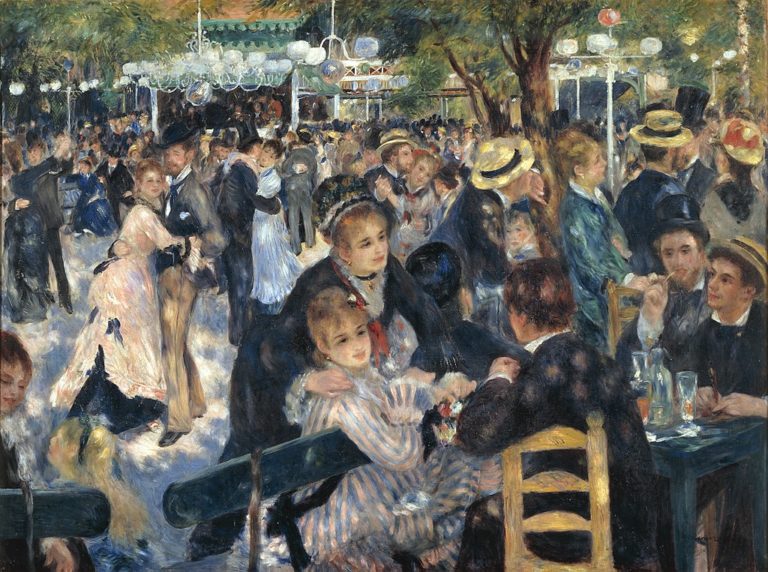

6) Au Musée d’Orsay: Bal du moulin de la Galette (Renoir, 1876)

Another modern idea is simply painting the new Parisian life.

In Bal du moulin de la Galette, for instance, Renoir does not paint a rich person’s portrait, or a historical event, or mythology – but a simple sunday afternoon in Montmartre, a sunny piece of everyday life.

Renoir was the only impressionist painter from a working-class family. He liked to paint happiness and sunny optimism. And the Parisian neighborhood of Montmartre. (His paintings are also part of the movie Amélie, that takes place in that area!)

** Le truc en plus **

It reminds me of Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont, a fun XIXth century French author, an elegant Black man born in French Guadeloupe, living the bohemian life in Paris, and writing about anecdotes around the city.

Click here to get his book: “Paris Anecdote” (French Edition)

*** **

Numbers:

- 1876 = mille-huit-cent-soixante-seize (“x” sounds like “s”)

- 1876 = dix-huit cent soixante-seize (“x” sounds like “z”, then like “s”)

And that’s our cue for revisiting these weird French numbers before one hundred!

- Soixante (60) (“x” sounds like “s”)

- Soixante-dix (70) (“60 and 10”)

- Soixante-et-onze (71) (“60 and 11”, hyphen because it’s below 100)

- Soixante-douze (72) (“60 and twelve,” etc. until 80)

- Soixante-seize (76) (“60 and 16”)

- Soixante-dix-neuf (79) (“60 and 19”)

- Quatre-vingt (80) (“Four twenty!”)

- Quatre-vingt-dix (90) (“80 and 10” = “four twenty ten”)

- Quatre-vingt-onze (91) (“80 and 11”, etc.)

- Quatre-vingt-dix-neuf (99)

- Cent ! (100)

Congratulations! I’m proud of you for going this far!

If you don’t remember everything, don’t sweat it – it will come with practice. But sometimes, you just need to see the rules once to really make it click together.

Now you can go deeper into other interesting topics. Click on the links to get to your next lesson:

- French Art Vocabulary: How to talk about it and give your opinion

- French Counting: An Essential Guide to French Numbers

- Fast French comprehension with La Normandie: the region of Monet and other impressionists

À tout de suite.

I’ll see you in the next video!

→ If you enjoyed this lesson (and/or learned something new) – why not share this lesson with a francophile friend? You can talk about it afterwards! You’ll learn much more if you have social support from your friends 🙂

→ Double your Frenchness! Get my 10-day “Everyday French Crash Course” and learn more spoken French for free. Students love it! Start now and you’ll get Lesson 01 right in your inbox, straight away.

Click here to sign up for my FREE Everyday French Crash Course

Tellement intéressant et serviable, merci ! Bien que Fabien, français et chiffres et étranges explications idiosyncrasiques = 🤯🤯 !!

Merci tout le même😊.

Superbe, Géraldine à part:

– en Belgique on dit septante et nonante mais pas octante

– les raboteurs = planers (one n) the tool is a plane (so that affects the pronunciation of planers)

J’ai vécu en Belgique pendant quelques années. Je préférais vraiment leur système de numérotation !

Bonjour Jane,

Merci beaucoup pour les précisions ! J’ai toujours du mal avec les différences entre la Suisse et la Belgique ! Ma grand-mère disait “nonante” et “octante” alors ça sonne “naturel” à mon oreille.

Merci Marion il est bon de pratiquer les chiffres.

Bonnes journée Anne

Beaucoup d’information ici ~ merci merci.

J’aime les peintures d’Édouard Cortès ~ le Paris

d’il y a cent ans – à peu près. Un temps après La

Belle Époque je crois, mais on a l’impression d’une

vie un peu plus élégante. Mais le Déjeuner sur

l’herbe et le scandale qui a suivi …….. !

Many artists face disapproval in their own time.

I very much like the work of the Scottish painter

Jack Vettriano, but his paintings have not really

been accepted by the British art establishment.

On the other hand, his work has been very

successful commercially ~ maybe that’s why

they don’t like him .. ?

A great lesson Géraldine, and many thanks ♫

This is a brilliant lesson. Thankyou. I did notice near the beginning you say ‘quatre-vingts’ but near the end ‘quatre-vingt’ ……?! Can it be either when on its own please?

I’ve never known the rule about “no s” in numbers like cent and vingt if something follows..merci bien!

Bonjour,

Les mots vingt et cent prennent la marque du pluriel à trois conditions :

ils doivent être multipliés (cinq-cents = 5 x 100);

ils doivent terminer le nombre (quatre-vingts, mais quatre-vingt-sept);

et ils ne doivent pas servir à indiquer le rang (deux-cents pages, mais la page deux-cent).

On écrira donc : cent-vingt (120) sans « s », car cent et vingt ne sont pas multipliés; trois-cent-quatre-vingt-dix (390) parce que cent et vingt ne terminent pas le nombre; mais deux-mille-sept-cents ans (2 700), car cent est multiplié et en fin de nombre.

On aura les années quatre-vingt (80) sans « s », car l’adjectif numéral ordinal après le nom indique le rang; mais quatre-vingts invités (80) avec « s » parce que le déterminant numéral cardinal devant le nom indique la quantité.

I hope this helps.

Fabien

Comme Une Française Team

Merci, Fabien. Ce leçon est magnifique avec sa combinaison de l’art et des nombres. Votre explication m’a aidé, aussi.

Je vous remercie mille fois😇

Merci boucoup(sp?) por le lessons Geraldine. Jelem. Dan